St Teresa of Avila – Saint, Mystic and Doctor of the Church

The Person Behind the Labels

St Teresa of Avila is often regarded as the quintessential Catholic mystic, famous for her visions and her experiences of religious ecstasy, not to mention reports of her body levitating while in prayer. And yet, the whole direction of her many religious writings was to de-mystify the religious experience. She preferred to focus instead on its potential to help people grow in love not only for God, but also for humanity. Though a Carmelite nun and a great reformer of the Carmelite way of life, she was known to frequently mutter “ God save me from pious nuns”, under her breath. While dedicated to prayer, she was also a practical woman who valued mundane activities like cooking and eating, remarking that “God lives also among the pots and pans.” She had a keen understanding of the challenges posed by a life of prayer. In her own account of her life she openly admits that she struggled for the first twenty years of convent life, revealing:

the depression she regularly felt on going into chapel to pray. And she describes how on many occasions, she waited impatiently for the clock to signal her release. (Williams p. 40)

Considering that Teresa had mystical experiences almost right from the beginning of her vocation, it would be mistaken to think that she wasn’t interested in prayer. Those experiences had simply expanded her horizons about its possibilities. This happened to such an extent, that the daily multiple rounds of communal recitation of prayers expected by her community, had become burdensome to her soul.

The News from Sixteenth Century Spain

Despite being born as Teresa de Cepeda y Ahumada to a well-to-do family in the town of Avila in central Spain, Teresa never quite fitted in to the society of her times. Her grandfather had been a converso, a Jewish convert to Christianity and this cast a shadow on the family’s social standing at a time when there was an obsession about the purity of blood lines among the nobility. The Spanish Inquisition had been set up only about forty years before her birth specifically tasked with uncovering conversos who were secretly still practising their Jewish faith.

Educated by Augustinian nuns, Teresa was deeply spiritual as a child and was hugely affected by her mother’s death when she was only twelve years old. However, by sixteen she had become by all accounts, a rather attractive young woman who enjoyed socialising with friends. Like many teenagers, she could be flirtatious. Her father was so concerned about her relationship with one young man that he had her sent to a convent for over a year to cool her ardour and quell the inevitable gossip in the town. On leaving the convent she spent three years at her uncle’s house where there was an extensive library. One day, sensing her unhappiness, he gave her Francisco de Osuna’s treatise on prayer The Third Spiritual Alphabet which proved to be the catalyst for the direction her spiritual life would take from then on.

Change of Direction

At the age of twenty-one without her father’s consent, she entered the Carmelite convent of the Incarnation in Avila. There, she continued to enjoy the social atmosphere shared by the nuns and was extremely popular. But a year after her profession of vows, her health broke down. There were serious fainting fits and unexplained fevers and by the following year of August 1539 she was even pronounced dead! Amazingly, she recovered but suffered from paralysis which didn’t completely leave her until she was into her early forties.

During these years she continued to study de Osuna’s treatise on prayer but also found time to read St. Augustine’s Confessions and St Ignatius’ Spiritual Exercises. During this same period she was taking spiritual direction from various Jesuit priests. She learned a lot about the foibles of human nature while in close contact with her fellow nuns during these difficult years. This provided her with a rich bank of experiences to draw on in her subsequent writings, which show her as both an acute observer of human psychology, and an eloquent guide to the thorny path of spiritual growth.

Teresa’s Complicated Relationship with Authority

Sixteenth century Spain not unlike the fourteenth century England of Julian of Norwich’s time, was still a period when men dominated public discourse. Women were expected to submit to the authority of men, were usually deprived of the sort of intellectual training open to men and were discouraged from roles that involved teaching or advising. The spiritual directors of women religious at that time were invariably men and so Teresa like Julian of Norwich in her writings, had to be very careful not to appear too clever. One way around this was to direct her writings towards other women religious while realising that it would all be fiercely scrutinised by the Inquisition for any evidence of heresy. This explains Teresa’s multiple declarations of self-doubt and excessive modesty. Here are some examples from The Interior Castle:

The truth is, the blessings are so abundant no one could understand them all, especially someone as dense as I am.

Someone with as little learning as I have will end up saying countless superfluous and even irrelevant things in order to make a single meaningful point.

Men of learning seem to get the theology without much effort. But we women need to take it all in slowly and muse on it.

… what hope can there be for a life as poorly spent as mine?

Who am I to be writing something to those who could just as well be teaching me?

It seems like Teresa is being very politically astute here. But her protestations of lack of ability are contradicted by her prodigious literary output. Before the crowning achievement of The Interior Castle written a few short years before her death at the age of sixty-four, she had already produced: The Way of Perfection, Spiritual Testimonies, Meditations on the Song of Songs, The Book of her Life and The Book of her Foundations. Her spiritual autobiography had already raised more than a few eyebrows among the exclusively male clerical authorities. In addition, her controversial reform of the Carmelite Order upset the establishment while showing her to be a consummate administrator in the ability to set up fifteen houses of the new reformed or Discalced Carmelites. In her latter years, this actual confidence in her own abilities gave her the freedom to caution her readers about the spiritual shortcomings of more than a few male spiritual directors:

Let’s begin with the torment of working with a spiritual guide who is so inexperienced and so prudent that there is nothing he feels sure about.

…at other times, if her advisor hasn’t had much experience, a soul like this may scare him and he will belabour the point and even turn something that should have been kept a secret into a public spectacle.

Having said that, Teresa always cautions that individuals should not just rely on their own experience but always be guided by a sensitive spiritual director.

The Interior Castle -What’s New?

This is a work that sets out a sort of spiritual road map for the soul’s journey. It shows a pattern of moving from discursive prayer where words and images are used to the prayer of quiet which we might equate with what many modern people understand as meditation, to the prayer of union or advanced infused contemplation where the action of God completely takes control of the soul. It follows the classic stages of spiritual progression of the purgative where we are purified of our imperfections to the illuminative where we achieve greater understanding of spiritual truths to the unitive where words fail to convey the depth of our experience and the sense of a personal ego falls away. A similar progression is described in The Cloud of Unknowing and the writings of St John of the Cross who was a contemporary of Teresa and a great friend and supporter.

The Interior Castle is a work of great literary as well as spiritual merit. It is characterised by the language of symbols, images and various types of allegory. At different times the soul is compared to a garden, a tree, a castle or a butterfly, while the sense of the Holy Spirit is conjured up by reference to the movement of water courses and fountains. The first three mansions or rooms of the castle deal with the purification of the soul. Not only is penance a requirement but Teresa advocates that people need to develop true self-knowledge. Often in religious life, the craving for materialistic things is replaced by the craving for holiness. In the second mansion we feel the tension between the way we live and the way God is calling us to live. In the third mansion we may experience a dryness or frustration in prayer and there can be a tendency to be shocked by the ways of the world.

The fourth mansion marks the transition from a life governed by the concerns of the ego to one where we begin to allow God to take over. Often there is a new kind of experience of God’s beauty. Prayer now is deeper and mostly does not involve words although, Teresa like the anonymous author of The Cloud of Unknowing advises that we can use some simple words to open ourselves to God’s presence. Our ability to focus on the presence of God becomes stronger but we are advised to avoid becoming too caught up in the practice and neglecting the mundane tasks of life.

In the next three mansions we see the action of God increasingly purifying the soul towards his likeness. Teresa reports on a whole range of extraordinary spiritual experiences such as visions, locutions where we ‘hear’ a message spoken to us as well as quite dramatic changes to the body including a slowing down of the heart rate and the apparent stopping of the breath and in some cases even levitation. Teresa is remarkably level-headed about all this, giving very clear indicators to check whether an experience is authentic or not. Many of these moments of spiritual ecstasy or rapture are also accompanied by intense pain which may be experienced at the purely spiritual or physical level. As we progress through these mansions we gradually surrender more and more to the will of God. Trials may persist in our lives but we weather the storms more quickly. The new inner stability in our lives prompt us to do good works for others and the earlier longing for death is replaced by a renewed commitment to being in the world and in the body. We see ourselves as part of a spiritual marriage or union with God with an unshakeable and fundamental conviction of his companionship.

What to Remember

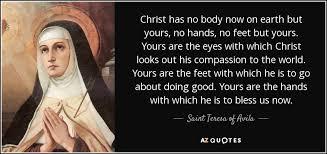

It is obvious from the directness and freshness of her writings that Teresa was a real flesh and blood individual who, while being a great contemplative was also a person who was very active in the world. Persistently poor health did not stop her in her attempts to bring a more authentic spirituality to the religious communities that she set up. Her political acumen saved her from the power of the Inquisition to have her silenced and even put to death. We also see in the progression of the writings, someone who, as she got older, became more compassionate towards her own sisters and more forgiving of their failings. Her life can be seen as the story of a spirited young woman who, at home in the world, by degrees allows her spirit to be infused and completely surrendered to the will of God. Like Julian of Norwich, her God is a god of great tenderness and forgiveness who is only waiting for us to approach him in prayer when we can no longer conceive of him through thoughts and words. Like so many mystics her writings are less about spiritual technique and much more about the quality of relationship. As she says herself;

And so my friends, I will end by suggesting that we avoid building towers without foundations. The Beloved looks less at the grandeur of our deeds than at the love with which we perform them.

This article is heavily indebted to these sources:

- The Interior Castle by St Teresa of Avila with an introduction and translation by Mirabai Starr Riverhead Books 2003

- Teresa of Avila by Rowan Williams Bloomsbury 1991

- “St Teresa – A Person for our Times” by Julienne McLean in Journey to the Heart (Ed. Kim Nataraja) Canterbury Press 2011