Julian of Norwich – Consolation for Difficult Times

A Lockdown Visualisation – 14th Century version

Picture yourself entering a bare room attached to a stone church. The room has just a small window adjoining the church and one small window looking out onto the roadway. It has no electricity or running water. You have taken a solemn vow of obedience and chastity. You have agreed to spend the rest of your life in this one room alone until you die and you understand that you will be buried beneath the floor of this room. As you place yourself in the room, a priest and some followers sing hymns and recite prayers taken from the Office of the Burial of the Dead. As they do so, the entrance to this room is permanently sealed. You are not allowed to touch another human again and you are expected to avoid contact with your family for the rest of your life. A volunteer from the local community will look after your practical needs.

Each day in winter time you will rise each morning at 3:30am and go to sleep at 7pm each evening. You will be expected to recite prayers which will take an average of 5 hours to recite each day. Apart from the prayers you are expected to keep silent as much as possible. From Easter to September you will receive two meals a day. You will not eat meat and on Fridays you will also avoid dairy. Your recommended main meal will be vegetable stew and you will always eat alone.

You will be expected to wear plain clothes and clothes of a rough texture next to the skin. As a woman your head will be covered at all times and you will not be allowed to wear a belt, jewellery or gloves. Your hair will be cut or shaved four times a year and you will be encouraged to wash regularly from a cold bucket of water. You are not allowed to send or receive letters. You may be financially supported by the local community or you may earn a little money by doing needlework such as the repair of vestments and altar cloths for the church. In time, you may offer spiritual advice to people that come to the small window facing out onto the street.

What I have described here is the recommended lifestyle according to the Ancrene Wisse for one who has decided to become an anchoress. This was a form of solitary religious life for women in the thirteen and fourteenth centuries and one embraced by Julian of Norwich at the age of thirty.

Who Was Julian of Norwich?

Not a huge amount is known about her background. We are not even sure of her name as the name Julian is most likely adopted after the name of the church in which she was so closely attached in Norwich. She was born in 1343 and may have been an orphan. As such, it is believed she may have been raised by nuns at the convent of Carrow, a few miles distance from Norwich. If so, she would have received a solid education for a girl of those times. She may or may not have been married and it is surmised that she may have had a number of children who along with her husband may have died due to the frequent outbreaks of the plague. At the age of 30 she had a near death experience where she was paralysed from the waist down and this lasted for 3 days after which, she made a dramatic recovery. While she braced herself for what she believed would be her impending death she started having visions, fifteen in a twenty-four hour period and one more the following day. These visions began with scenes from the Passion of Christ where she found herself at times in conversation with the image of Christ. This very intense experience prompted her to become an anchoress and shortly afterwards she wrote a short account of her experiences.

What Was She Known For?

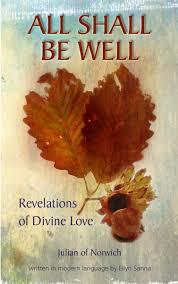

Julian spent the next twenty years reflecting on the significance of what had happened to her and then wrote it down as the text we now know as Revelations of Divine Love. She was the first woman to write in the English of the time. Normally, texts would have been written in Latin. As a woman she would not have been given the opportunity to learn Latin so she regarded herself as uneducated. However, her writings show clearly that this is not really the case as they suggest someone who is theologically well informed and a writer of considerable skill and insight. The fact that she wrote them in English meant that her thoughts reached a much wider audience than if she had written in Latin. She became well known in her own lifetime and people sometimes travelled long distances to seek her spiritual advice. She lived into old age (by the standards of the times), and died when she was 73 or 74.

Why Were Her Revelations So Unusual?

At first glance Julian’s writings are not unusual for the time. They begin with a description of the suffering Christ. Dwelling on the passion of Christ as a meditative exercise was widely encouraged in those days to instil a sense of sorrow for one’s own sins and an appreciation of the sacrifice that Christ made on our behalf. There was also in this period, a strong emphasis on original sin, the sinfulness of humankind in general and a view of the body as something that holds the soul back from spiritual attainment. Allied to this was an emphasis on God’s anger and the punishment that awaits those who do not follow his teachings. People were encouraged to be vigilant of the devil and the distinct possibility of ending up in the fires of hell because of their sinfulness.

Throughout the Revelations of Divine Love, Julian is very careful not in any way to be seen to contradict the teachings of ‘Holy Mother Church” and repeatedly reminds us of her lack of education or knowledge of theological matters. In these patriarchal times, it was considered inappropriate for women to view themselves as teachers capable of theological insight. But the general tone of her writings is one of consolation and re-assurance concerning God’s forgiving and loving nature. She takes what might now be regarded as a feminist perspective: regarding Christ as the mother of humanity, and says that not only did Christ at the incarnation, enter the womb of Mary but that humanity itself is placed in the womb of Christ.

In line with this then Julian held a benign view of the human body since it was created by God and assumed by Christ. In her view, the bodily senses are a precious part of ourselves that support the soul in its eventual redemption.

Here is a taster of some of Julian’s words:

Regarding sin: “God also revealed that sin shall be no shame to man, but his glory.” p. 87

Regarding judgement and forgiveness: “Do not accuse yourself too much, judging that your tribulations and your unhappiness is all your fault …” p. 155

Regarding Spiritual Consolation: “Our Lord takes care of us very lovingly when it seems to us that we are almost forsaken and abandoned” p. 89

“For I saw truly that it is against the nature of his power to be angry, and against the nature of his wisdom, and against the nature of his goodness. God is the goodness that cannot be angry, for he is nothing but goodness.” p. 100

“God wants us to understand and believe that we are more truly in heaven than on earth.” p. 121

Two Aspects of Her Writings that are Strikingly Modern

Julian of Norwich shows an acute understanding of human psychology. She makes the case for the importance of self-knowledge: ‘…we can never come to a full knowledge of God until we first know our own soul clearly … ‘p. 123. And this self-knowledge cannot be gleaned by reason alone: ‘But our fleeting life that we lead in our sensory being does not know what our self is, except through faith.’ p. 99 While her advice on how to manage challenging emotions states:

“And therefore it is not God’s will that we should be influenced by feelings of pain to sorrow and grieve over them, but to quickly pass beyond them and hold on to the endless joy that is God.” p. 61

A modern secular translation might read: ‘Avoid ruminating over your problems and focus on the positive.’

The second aspect of her writings that share a modern sensibility is her concern for accuracy of reporting.

All this was shown in three ways: that is to say, by bodily sight, and by words formed in my understanding, and by spiritual vision. But I neither can nor know how to disclose the spiritual vision as openly or as fully as I would wish. p. 52

Julian is clearly aware that her experiences may be dismissed as the fantasies of someone who is psychologically unstable and invokes divine authority to make her case:

Then our good Lord revealed words to me very gently, voicelessly, and without opening his lips, just as he had done before, and said very lovingly, “Be well aware now that what you saw today was no delirium, but accept it and believe it, and hold to it, and comfort yourself with it, and trust it, and you shall not be overcome.’ p. 143

Even though she is reporting on an essentially private inner experience she is keen to state precisely, how the experience was communicated to her, so that we might consider her as a credible witness.

The Relevance of Julian of Norwich Today

The popularity of Julian of Norwich’s writings have been steadily growing in the last few decades. T.S. Eliot references her in his poem “Little Gidding” in 1943. Since 1980 she has been commemorated in the Anglican Church with a feast day on 8th of May. Although not formally canonised a saint in the Roman Catholic Church, she is popularly venerated by Catholics and has a feat day on the 13th of May. In 2013 the University of East Anglia honoured her by naming its new study centre the Julian Study Centre. And in March 2020 during the height of the Covid-19 pandemic, Julian’s years as an anchoress have been a consolation to people forced to self-isolate. Perhaps the most well-known saying from her Revelations of Divine Love is particularly needed in these uncertain times:

‘ … all shall be well, and all shall be well, and all manner of things shall be well’

p. 74

(All quotations taken from Oxford World Classics 2015 translation by Barry Windeatt)