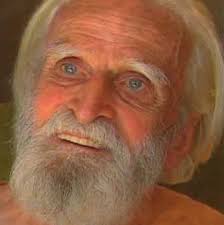

Bede Griffiths – The Marriage of East and West

I sit here on the veranda of my cell, watching the sun set behind the trees, and recall the day, nearly fifty years ago, when I watched the same sun setting over the playing-fields at school. My cell is a thatched hut surrounded by trees. I can listen to the birds singing, as I did then, and watch the trees making dark patterns against the sky as the light fades, but I have travelled a long way in space and time since then.

(Return to the Centre p.9)

These are the opening words of English Benedictine priest and monk Fr Bede Griffiths’ ground-breaking Return to the Centre – a series of meditations on the Christian faith in the light of Hinduism and Buddhism, published in 1976. They recall a transformative mystical experience in his life while at boarding school as a seventeen year old:

I remember now the shock of surprise with which the sound broke on my ears. It seemed to me that I had never heard birds singing before and I wondered whether they sang like this all the year round and I had never noticed it. … I remember now the feeling of awe that came over me. I felt inclined to kneel on the ground, as though I had been standing in the presence of an angel; and hardly dared to look on the face of the sky, because it seemed as though it was but a veil before the face of God.

(The Golden String p. 1)

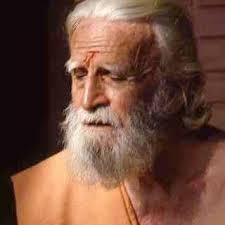

That initial experience led a very shy, rather repressed Edwardian who spoke with a cut glass English accent, to become an internationally recognised promoter of inter-faith dialogue. A man who while making his home in the south of India, dressed in the kavi – the robes of a Hindu ascetic or sannyasi and who adopted the Hindu name of Swami Dayananda (the bliss of compassion). But by 1991 less than two years before his death, he was not without his critics. There were some Hindu conservatives who accused him of cultural appropriation, while there were Catholic conservatives who felt he had gone too far:

While we cannot form a judgement about Bede Griffith’s personal sanctity or the depth of his spiritual experience, we can form a critical judgement about his theology

(Robert Fastiggi & Jose Pereira in “Crisis”)

Fastiggi and Pereira’s theological criticisms may not be unreasonable, but there is a churlishness in their lack of recognition of his sanctity. This sanctity and depth of contemplative experience was widely evident, not only in Shantivanam, the ashram in Tamil Nadu that Griffiths led from 1968 onwards, but also on his many visits to the U.S., Europe and Australia over the years that followed. But to properly understand that sanctity we need to appreciate the long road he had travelled over the course of his life.

From Genteel to Monastic Poverty

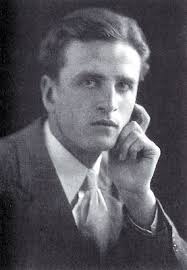

Born as Alan Richard Griffiths in 1906 to a middle class family in Walton-on Thames, Surrey, the young Alan led what he later remembered, as a very happy childhood in the English countryside. This was despite his father Walter’s experience of having being cheated in business, an experience that he never recovered from, so that Alan’s mother became the sole breadwinner for the rest of Alan and his three siblings’ upbringing. His parents were quite devout Anglicans. Even though they did not press their children into religious practice, Alan by age eight could be found “… sitting up in bed on Sunday nights, conducting the evening service , chanting the responses and saying the prayers himself.” ( Beyond the Darkness p.6). He was a bright boy, always at the top of his class so it was no surprise that he would win a scholarship some years later in 1925 to attend Oxford University. At Magdalen College he initially studied Classics and subsequently moved to English literature. While there he became friends with C.S. Lewis and this friendship continued over many years. He graduated in 1929 with a degree in Journalism which proved useful as he subsequently wrote twelve books and numerous articles for periodicals and journals.

Soon afterwards he set up home with two friends in a simple cottage in Eastington in the Cotswolds. It had no electricity or running water but this suited them just fine as they were all trying to escape what they regarded as the de-humanising effects of modern technology. They milked cows and planted vegetables to support themselves. In the evenings they read the Bible but as literature rather than as the Word of God. Their religious sense was more that of the Romantic nature poets than of organised religion. However this experiment in frugal living ended before the year was out when one of them went off to be married. Alan then began to take an active interest in Anglicanism and even considered becoming a minister of the church. Having taken the advice to first do some voluntary work among the poor in the slums of London, he had a spiritual crisis. He felt he wasn’t cut out for this active type of ministry.

Influenced by the writings of Cardinal Newman, he had a kind of spiritual breakthrough and converted to Catholicism in 1931, much to the chagrin of his mother and staunchly unionist friend C.S. Lewis. By 1932 he was a novice at Prinknash Benedictine monastery and now known under his new religious name of Bede. Initially he was disappointed by the lifestyle of poverty, chastity and obedience because the regime was much more comfortable than what he had experienced voluntarily at Eastington. By 1940 he had become a priest and during this period he took up the study of Eastern religions in earnest. In 1947, he was sent by his Abbot to Farnborough in Hampshire to be Prior to a smaller monastery.

Over the four years there, he developed a reputation for his kindness to his fellow monks and hospitality towards guests, but he struggled with the practicalities of running a monastery and a working farm. It is believed that financial difficulties led to his Abbot in 1951, suddenly removing him from his position and sending him to Pluscarden Abbey in Scotland, where he would no longer be Prior. Chastened, Fr Bede never complained and became a very accomplished Master of Novices. Four years later, his fifteen years as a cloistered Benedictine monk were about to come to an end.

The Call of India

In 1955 Fr Bede had met a visiting Benedictine monk Fr Benedict Alapatt who harboured the desire to set up a Benedictine monastery in India. Fr Bede was enchanted by this idea and shared his idea of nurturing the seeds of a contemplative way of living the Christian faith in India. However, his Abbot initially opposed the idea remarking that “there is too much of Bede Griffiths’ will in this”. In the end his Abbot relented and Fr Bede set sail with Fr Bendict for India at the age of 49 claiming that, “I am going to discover the other half of my soul”.

After a few months of finding their feet, Fr Bede and Fr Benedict settled in Kengeri near Bangalore but continued to observe the rule of the Benedictines even though they were now technically under the authority of the local bishop. Three years later, after some tension between Fr Benedict and himself, Fr Bede moved on to Kurisumala in a mountainous region of the state of Kerala, remarking that the settlement in Kengeru had been “too Western”. Here, with a Cistercian monk, Fr Francis Acharya, he set up a Christian ashram closer to the spirit of Hinduism. There was lots of hard physical labour to be done to get things off the ground, but Bede Griffiths was no stranger to hard work. Initially they had little money, but the combination of a donation from a local convent and donations from England set them on their feet.

Both men adopted the traditional garb of the Hindu ascetic or sannyasi and celebrated the Christian liturgy according to the Eastern Syrian rite which prevailed in this part of the state of Kerala. They set up a cattle-breeding farm to create an income and later established a pharmacy where they offered traditional remedies to the people of the surrounding villages. Within less than two years they were joined by sixteen men who wished to become monks. Along the way, they set up various cottage industries and educational initiatives to support the local people. Gradually, through Bede’s writings he was becoming internationally well known. He travelled to various conferences and increasingly, people came to visit him at Kurisumala.

The Move to Shantivanam

However, Fr Francis and Fr Bede could see that they held increasingly separate visions of where they were going. Fr Francis wanted to integrate the foundation within the existing church in the region, while Bede wished to have an ashram that provided a different model of church – one that was less intellectual and more intuitive in its approach to reaching the Divine. And so it was that in 1968 Bede Griffiths took over the running of Saccindananda Ashram also known as Shantivanam in Tamil Nadu. Replacing two earlier French priests, Frs Monchanin and Henry Le Saux, one of whom had died and the other who wished to live the life of a hermit, Bede was delighted with the new venture stating: “ I have never known a place where I have felt so perfectly at home”.

Christianity in the Light of Other Faiths

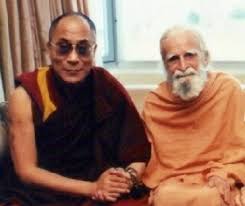

Though Bede Griffith’s immersion in eastern culture, beliefs and practices began back in England in the 1940s, it intensified during his nearly forty years in India. Much of his life was spent reflecting upon and writing about the Christian faith seen through the prism of Hinduism and Buddhism. But he was attuned too, to the beliefs and practices of many other faiths which at some level, could be seen to be manifestations of the action of the Holy Spirit. While the ideas of Thomas Merton towards the end of his life, showed a similar openness, Griffiths went beyond ideas in the way he embraced Hindu religious practices and wove them into the Christian liturgy, as it was celebrated at Shantivanam Ashram.

His move to Shantivanam came just a couple of years after the close of the Second Vatican Council, which officially gave people like Griffiths encouragement to explore inter-faith dialogue:

The catholic church rejects nothing of those things which are true and holy in these religions … It therefore calls upon its sons and daughters … to recognise, preserve and promote those spiritual and moral good things as well as the socio-cultural values which are to be found among them.

(Nostra Aetate Decree of the Ecumenical Council)

Bede Griffith’s wide reading and depth of spiritual practice enabled him then to say something quite bold for a an ordained Catholic priest:

I have to be a Hindu, a Buddhist, a Jain, a Parsee, a Sikh, a Muslim, and a Jew, as well as a Christian, if I am to know the Truth and to find the point of reconciliation in all religion. (Return to the Centre p. 71)

Note that Griffiths is not suggesting that every aspect in each religion is of equal value. He recognizes that there may be contradictory beliefs and practices but he urges us to:

… discern among these conflicting and partial views the principle which unites them, which transcends their differences and reconciles their conflicts. (Return to the Centre p. 107)

At no point does Griffiths suggest that the Jesus of Christianity, the Krishna of Hinduism and the Buddha of Buddhism are interchangeable, but he sees value in all three in pointing the way: “If Krishna had never existed, it would make no real difference. He is for ever a symbol of love incarnate.” (Return to the Centre p. 84) While in comparing Christ with the Buddha he says:

The teaching of the Buddha and the teaching of Christ both have this infinite depth, because they derive from the one source, the ultimate Truth, the Ground of being itself. (Return to the Centre p. 120)

Even when it comes to the core of Christian doctrine, Griffiths sees exciting parallels between the Holy Trinity and the Hindu concept of Sacitananda – the Father, Son and Holy Spirit equated with the Hindu relationship between Being (sat), consciousness (cit) and bliss (ananda). But it is probably only through extensive contemplative practice that the relationship between the two, can be intuited rather than grasped intellectually. However, Griffiths himself, does not concern himself too much with a method of practice.

Unlike earlier Christian mystics he is not eager to emphasise technique or to present a map of the mystical journey. He does however tell us that he sometimes recites the words of the Jesus Prayer when he meditates: “Lord Jesus Christ, Son of God, have mercy on me, a sinner”. But when asked for advice about how to meditate he often recommended the use of a Christian mantra such as Maranatha as developed by fellow Benedictine John Main, whom Griffiths much admired. (Beyond the Darkness p. 173)

The Shortcomings of Religious Institutions

For Bede Griffiths, the Catholic Church although founded by Christ, has a markedly Graeco-Roman structure which was built on an original Jewish template. As such, it now struggles to appeal to those of significantly different cultural backgrounds. For this reason Griffiths regards the process of inculturation (whereby religious rituals are adapted to local cultural norms), as completely justified in the context of preaching the gospel in Asia. Moreover, the Church is also failing in the west because of the unprecedented cultural changes of the twentieth century. He argues that its teaching needs to be renewed in much the same way that the teachings of Jesus were a development of the Law as taught by the Old Testament prophets.

The structure of doctrine and the ritual and organization which it has inherited are no longer adequate to express the divine Mystery, like those of Israel in the time of Christ. (Return to the Centre p. 110)

A Deepening Into the Mystery

Over his many years in India, Bede Griffiths drew people to him from all over the world. Despite his need for solitude as a contemplative, he retained a welcoming attitude to guests, often seeking them out on their arrival. This was something he had first practiced as a Guest Master at Prinknash Abbey so many years earlier. People would often consult privately with him about the difficulties and direction of their lives. He was not known for his advice, which he rarely gave, but instead for the quality of his compassionate presence as he listened. This experience was also shared by the many people who met him as he travelled the world in his latter years:

… As soon as he walked in there was something very special and very different about him …

… I knew I was in the presence of a saint …

… It was as if Christ was walking the earth … Meditating with him was like being in an infinite ocean.

… [I felt] real peace, joy, and this very lightness of being … (Beyond the Darkness p. 242)

In February of 1990, Bede Griffiths had a major stroke which left him incapacitated for about a month after which he made a remarkable recovery. The event was not just a medical emergency. For Griffiths it was a mystical experience, the sense of being with Jesus on the cross and having to surrender to death. Then he had an inspiration to “Surrender to the Mother’. In doing so he “ … had an experience of overwhelming love. Waves of love sort of flowed out of me”. (Beyond the Darkness p. 230) This experience of overwhelming love stayed with him for his remaining few years. He made sense of it all by considering that he had finally opened up to the feminine principal in himself, having spent most of his life ruled by his more masculine, rational side. As his biographer remarked:

More and more he began to feel the masculine mind dissolve and the intuitive feminine side begin to take its rightful place … and he found himself, though it had not been his normal custom, praying the ‘Hail Mary’ constantly … (Beyond the Darkness p. 230)

One of the concepts that most influenced Griffiths throughout his mature years was the concept of the non-dual. Expressed most clearly in the Hindu Advaita Vedanta tradition, although one can find evidence for it too in Buddhism and even in Christianity (‘That they may all be one.’ John 17:21). In his life, Bede Griffiths strove to marry the spirituality of east and west into one and to unite the masculine rational and the feminine intuitive within himself; while advocating that the same unification was needed within the Catholic Church itself if it was to remain relevant to the modern world.

While Bede Griffiths the man, monk and mystic died on the 13th of May 1993 he lives on in the memories of those who encountered him:

What hit me most was that in my normal rush and bustle of the morning to walk into Father Bede’s presence was like hitting a clear wall of stillness. His quietness and stillness was all pervading (Joan Terry in Beyond the Darkness p. 252)

The remarks of Fr John Kilian, an American priest, who visited Fr Bede in his dying days provide a fitting end to this exploration of Bede Griffiths:

I have never seen him so affectionate and loving. He draws people to him and hugs them … It was as if the other part of his soul that he had come to find in India broke through the proper English manner like a torrent of love and joy. (Beyond the Darkness p. 260)